"Invisible" is a common value in design; works that get out of the way of the audience and behave like they aren't even there. But "simple" isn't the only kind of good design. A piano is a complex instrument, and a grand piano dominates any aesthetic space it's placed in. This isn't a flaw. Pipe organs can take up so much presence in their space that they literally become the architecture, some cathedrals featuring whole walls of pipes. And the keyboards are complex; they take time and attention to master. But these complex, dominating designs can do things that no invisible design could accomplish when the operator pulls out all the stops.

My Division III project at Hampshire College, “Memetic Engines of Anticapitalism,” is a complex work. It was a year-long art, philosophy, and media theory project culminating in a gallery installation featuring three projects illustrating the ideas in the work, and a literal wall of text, laying out the argument I made in plain English.

When we try to teach difficult things, we often try to convince the people we’re teaching that, actually, the thing is easy. Doing so results in a predictable path to failure: the student jumps in and tries to learn, encounters difficulty, assumes that they aren’t smart enough to learn the thing, because it’s supposed to be easy.

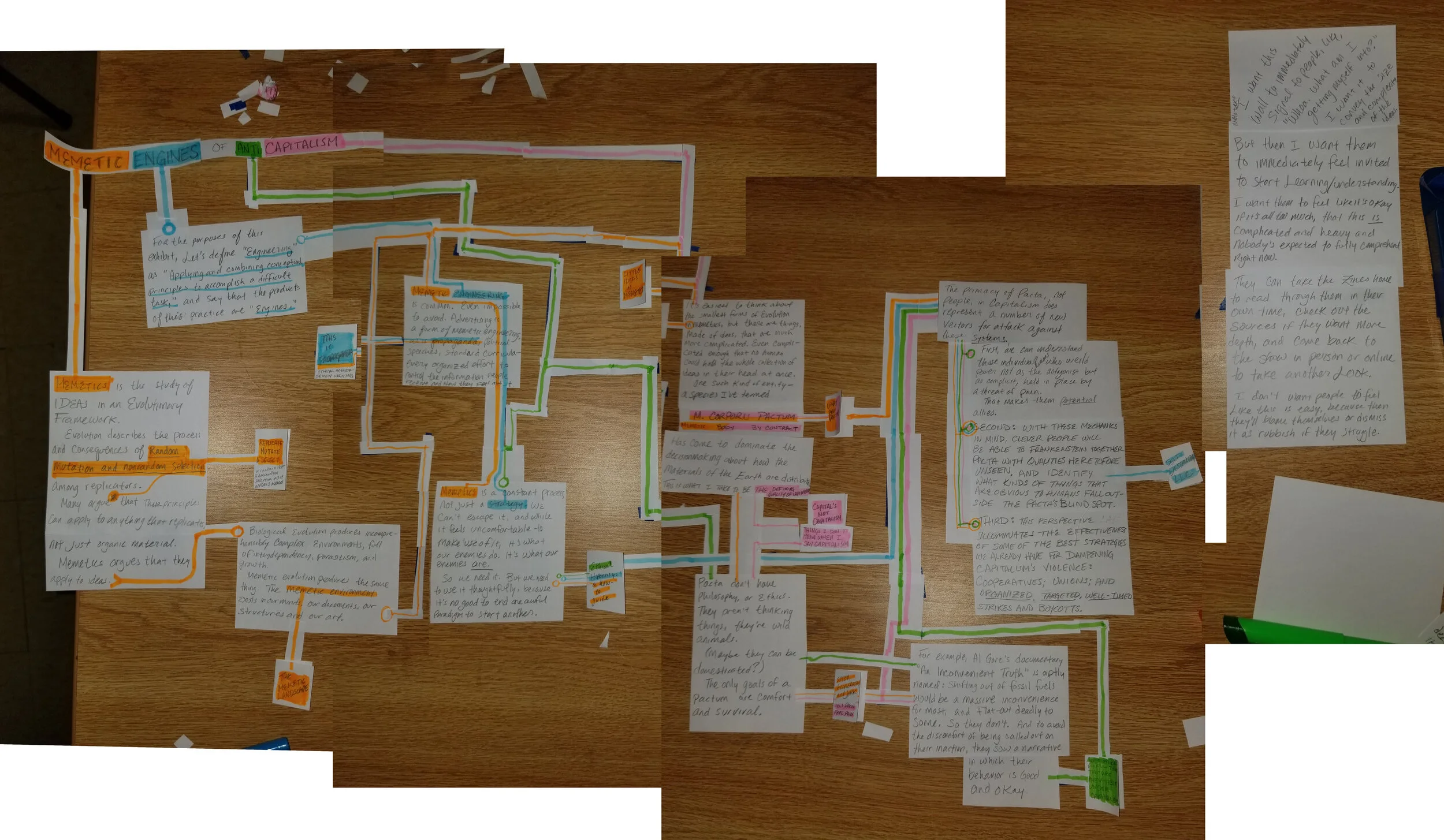

From my notebook leading up to proposing this project, at the end of my Division II at Hampshire. Shared mainly to illustrate how much like Lovecraftian ramblings this topic seems when first approached.

I didn’t want anyone to think that engaging with this installation was going to be easy. I wanted them to have two experiences in immediate succession: first, that the ideas in this installation are complex and challenging; and second, that they know exactly where to start in order to understand.

After months of notemaking, drafting, and discussion with my peers and advisors, this map of notes became the first draft of what would be the form of my installation.

The project was a huge success in this regard. I had struggled to explain these ideas to anyone for the entire year leading up to the installation, but in that gallery nobody was confused. (The fact that the project was a year-long effort to make very difficult ideas accessible in the context of exactly one room has made it difficult to, subsequently, explain what the project was, though.)

“I never understood what people were talking about but you made it so obvious, I felt smart. ”

The wall pictured at the top of this page is the most visible space in the Hampshire Art Gallery. It can be seen through the glass walls and door, from the open walkway overhead, from the stairs into the building. I decided early in the project that I was going to use that wall to make my central argument.

To that end, I made a 3D model of the gallery in Autodesk Fusion 360. My installation only occupied the first section of the space, with two other installations in the middle and back of the gallery at the same time, but I made a complete model of the space to share with other students.

This model is still used by Hampshire’s art students and gallery director to plan installations.

Apart from the wall of text, there were three components to my installation: art projects meant to illustrate the techniques and ideas I described. One is a series of limited-edition prints, modeled on corporate share certificates; a future-historical museum installation piece, depicting the campaign of a third-party political movement in the 2030s; and an alternate reality game about the differences in sensory experience between individual humans and large organizations.

A more complete archive of the project, with the full text of the wall, is online at memeticengines.com.